Race, Art and Evolution

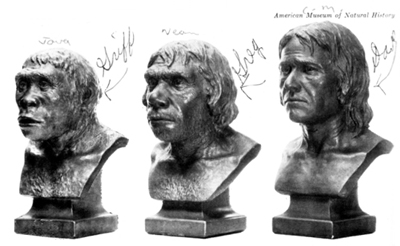

The sculpted busts of “early man” by J. H. McGregor, and the paintings of Neanderthal flint workers and Cro-Magnon artists by Charles R. Knight, alchemized imaginary beasts of centuries past into icons of progress that carried the imprimatur of science. But the narrative they supported was conflicted from the start. Created between the years 1915 and 1920 under the guidance of Henry Fairfield Osborn, director of the American Museum of Natural History, the images were designed to both celebrate scientific progress and alert visitors to the museum’s “Hall of the Age of Man” of an impending eugenic crisis. Osborn believed humans had reached an evolutionary peak in the caves of Lascaux, but that racial mixing was threatening to drag the species back.

It was a downer of story, and the visiting public, or at least the white public, happily skipped past it. Instead they saw in Knight and McGregor’s images visual confirmation of their own racial, cultural and scientific superiority.