October 6, 2009

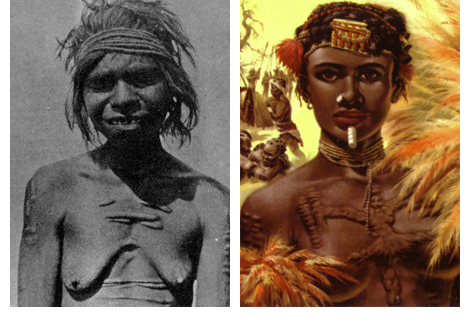

These images both depict ceremonially scarred women, face on, naked at least to the waist. The one on the left is from a popular college textbook from the 1940s. The one on the right is from a Men’s Adventure magazine, otherwise known as a “sweat” or “armpit” pulp, from the 1950s.

In this article I suggest, despite their quite different contexts, these images served a common purpose. They invited the viewer to enter a protected sphere where fantasies of superiority and domination were reinforced and could be comfortably indulged.

THE COMMON TROPES

Though challenges to what we now view as stereotypic constructs of race, class and gender started creeping into biology texts and popular science books in the 1930s, conservative publishing practices and generational inertia assured that prejudices based on a belief in genetically determined hierarchies survived well past their sell-by date. This created a period – from the later 1940s through the early 1960s – of overlap in the visual tropes used to illustrate these hierarchies in blue-collar publications like the pulps and white-collar publications like college textbooks.

The following is a comparative analysis of the visual tropes employed in Men’s Adventure magazines and college biology textbooks from the middle of the twentieth century.

MEN’S ADVENTURE MAGAZINES

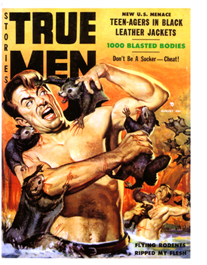

Though the genre’s roots were in “true story” magazines published from the 1920s, Men’s Adventure magazines, under queer-to-the-modern-ear titles like True Men, Male, Rugged Men, Man’s Conquest, Peril, Stag, Rage, Fury and Climax, thrived in years following World War II. Though the war was tragic beyond comprehension, it was also the most thrilling, most morally black and white, most celebrated adventure its participants would ever experience. Compared to the factory floor 50’s to which most soldiers returned, World War II, at least through the smoky glass of nostalgia, was a time of heroics, where the individual, particularly the individual blue-collar white guy, saved the day.

Though the genre’s roots were in “true story” magazines published from the 1920s, Men’s Adventure magazines, under queer-to-the-modern-ear titles like True Men, Male, Rugged Men, Man’s Conquest, Peril, Stag, Rage, Fury and Climax, thrived in years following World War II. Though the war was tragic beyond comprehension, it was also the most thrilling, most morally black and white, most celebrated adventure its participants would ever experience. Compared to the factory floor 50’s to which most soldiers returned, World War II, at least through the smoky glass of nostalgia, was a time of heroics, where the individual, particularly the individual blue-collar white guy, saved the day.

Men’s Adventure magazines positioned the modern world, with its shifting moral standards and social hierarchies, as progressively out of control, and positioned the muscular white male as its rescuer and redeemer. But just below the surface lay a seething resentment, and a resultant desire to salve insecurities and restore a “natural” order through tales of humiliation and domination – of the environment, the economically advantaged, the morally “liberated,” the “savage” races, and progressively through the 1960s, women.

Men’s Adventure magazines positioned the modern world, with its shifting moral standards and social hierarchies, as progressively out of control, and positioned the muscular white male as its rescuer and redeemer. But just below the surface lay a seething resentment, and a resultant desire to salve insecurities and restore a “natural” order through tales of humiliation and domination – of the environment, the economically advantaged, the morally “liberated,” the “savage” races, and progressively through the 1960s, women.

Though Playboy debuted in 1953, and was copied by many publishers after, Men’s Adventure magazines proved the better sellers at newsstands, perhaps because they provided “pornographic” thrills in a publicly acceptable package.

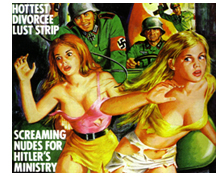

However, though the imagery in Men’s Adventure magazines, particularly into the 1960s, could be horrifying in its misogynistic sadism, it was often charming in its protective prudishness. While Playboy exposed breasts and bottoms, and promoted women as purchasable commodities, pulps from the 50s into the 1960s positioned women, at least American women, as “damsels in distress,” buxom and delicious, but with bottoms covered and nipples carefully hidden in countless clever ways. True, many of the magazines included pin-ups, photos of real women. But these too usually titillated without exposing the, er, tip.

However, though the imagery in Men’s Adventure magazines, particularly into the 1960s, could be horrifying in its misogynistic sadism, it was often charming in its protective prudishness. While Playboy exposed breasts and bottoms, and promoted women as purchasable commodities, pulps from the 50s into the 1960s positioned women, at least American women, as “damsels in distress,” buxom and delicious, but with bottoms covered and nipples carefully hidden in countless clever ways. True, many of the magazines included pin-ups, photos of real women. But these too usually titillated without exposing the, er, tip.

The sweats did not give way to down-market newsstand porn until the mid-1970s, when the dueling Freudian foci of bodies and bullets split into separate streams – spread-eagle rags and the mercenary magazine.

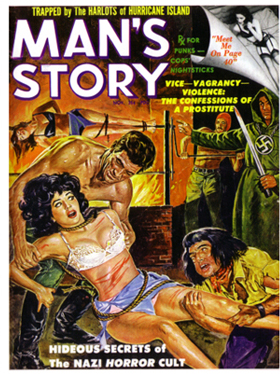

Until that time, the sweats navigated the tension between an ego-driven desire to humiliate women and the narrative need to protect them. Ultimately, the women between the pulps’ covers were there not to be ravaged but saved, or if “fallen,” redeemed, as in the story pimped with the headline: “13 Brothel Girls Who Fought to RESCUE PARIS!” Even “savage” women, though painted with more flesh exposed, were generally portrayed as attractive and worth rescue.

The visual tropes employed by the pulps were comically stereotypic, but they generally portrayed the enemy as worthy.

Yes, there were ugly tropes, all threatening to rape and kill the “damsel in distress” or castrate and kill her would be rescuer: the “hideous dwarf,” the “Nazi torturer” (both male and female), the “cave man” and “wild nature” (the bugs and crabs and spiders and piranha and bears and panthers and monkeys and flesh ripping weasels that swarmed and attacked the shipwrecked and the lost, male and female alike). But there is no heroism in defeating a weak and unworthy opponent, and the ugly were not there simply to be mocked. Even “savage” men, though almost always “blackened” relative to even their female kin, were generally depicted as solid and strong.

Yes, there were ugly tropes, all threatening to rape and kill the “damsel in distress” or castrate and kill her would be rescuer: the “hideous dwarf,” the “Nazi torturer” (both male and female), the “cave man” and “wild nature” (the bugs and crabs and spiders and piranha and bears and panthers and monkeys and flesh ripping weasels that swarmed and attacked the shipwrecked and the lost, male and female alike). But there is no heroism in defeating a weak and unworthy opponent, and the ugly were not there simply to be mocked. Even “savage” men, though almost always “blackened” relative to even their female kin, were generally depicted as solid and strong.

The same could not be said of college textbooks.

COLLEGE BIOLOGY TEXTBOOKS

Biology textbooks of course appealed to a different audience than Men’s Adventure pulps. Yet they deployed the same visual tropes.

Missing was the “Nazi torturer.” Why no Nazis? One could speculate that biologists, embarrassed by Nazi “misapplication” of the eugenic creed they’d spent three decades promoting, perhaps thought it best to just let that sleeping dog lie.

However, the other tropes – the “hideous dwarf,” “wild nature,” the “cave man” and the “savage – had starring roles.

The “hideous dwarf” was everywhere, sprinkled liberally about to scare students away from non-eugenic marriages. The “freaks,” the “pinheads” and “lobster boys” of the American sideshow already in decline, were on full display in many high school and college texts, yanked from even the minimal protective custody of carnival culture.

The “hideous dwarf” was everywhere, sprinkled liberally about to scare students away from non-eugenic marriages. The “freaks,” the “pinheads” and “lobster boys” of the American sideshow already in decline, were on full display in many high school and college texts, yanked from even the minimal protective custody of carnival culture.

“Wild nature” was also everywhere, with the biologist pitted against bad germs and bad genes in an ongoing battle to control the elements and improve the species.

“Cave men” too were common, sometimes depicted as brutal and dim, but more often as cooperative and protective, our artistic and religious forbearers. The more “cultured” ones were always white.

“Cave men” too were common, sometimes depicted as brutal and dim, but more often as cooperative and protective, our artistic and religious forbearers. The more “cultured” ones were always white.

The “savage” was also common, and of course always black. Variously labeled as “Ethiopian,” “Oceanic” or “Pygmy,” the “savage” always fell to the bottom of the page in textbooks. Typically singled out as the “most primitive” were the “Autraloids,” or Australian Aborigines, a group so backward, so intellectually challenged according to one author, they didn’t know enough to wear clothes or make huts or come up with general intellectual abstractions like the class “tree.”

so intellectually challenged according to one author, they didn’t know enough to wear clothes or make huts or come up with general intellectual abstractions like the class “tree.”

From the 1940s into the 1960s, Aborigines were usually listed as one of four main “subspecies” or racial lines, but were almost always singled out as “primitive,” with authors stating that members of the race were physically and mentally different from modern humans, “with little aptitude for civilization.” In Man and His Biological World (1952), the authors wrote, “the native Australians, the Tasmanians, and the African Bushmen, have never evolved much above the Neanderthal level of intelligence and culture” (469).

Here’s where comparison with the pulps gets interesting.

Where the pulps tended to pump up the ferocity and strength, if not cunning, of the “savage” in order to amplify the drama of the rescue, biology textbooks cast the “savage” less heroically. At times the “savage” exemplified “barbarian virtue.” In M. W. de Laubenfels’s Life Science (1949), “savages” were “Apollos,” strengthened by their vegetable free diet of meat, blood and milk. Much more commonly, “savages” were cast as children, primitive and silly.

Finally, the “damsel in distress” trope, central to the pulps, had no role to play in biology textbooks. One could almost say that women had no role in biology.

Humans were indexed under “Men.” The male silhouette served to house the maps of the major systems, circulatory, digestive, endocrine and nervous. Reconstructions of human ancestors were always male.

There was reproduction, of course, and women could hardly be excluded from the discussion of that topic. But there were no images of real pregnant women or photos of real childbirth, only headless illustrations of ovaries, fallopian tubes and uteruses or plastic cross-section models. One remarkable drawing from the 1940s, purporting to simply trace the parallel development of the male and female sex organs, culminated with an illustrated crotch shot that could have found a comfortable home in a 70’s porn magazine.

There was reproduction, of course, and women could hardly be excluded from the discussion of that topic. But there were no images of real pregnant women or photos of real childbirth, only headless illustrations of ovaries, fallopian tubes and uteruses or plastic cross-section models. One remarkable drawing from the 1940s, purporting to simply trace the parallel development of the male and female sex organs, culminated with an illustrated crotch shot that could have found a comfortable home in a 70’s porn magazine.

There were many photographs of women, at least white women, performing health examinations, peering into microscopes, giving instruction to groups or simply behaving in a healthy fashion, by say riding a bike. However women more often then men were pictured as young, naked, infirm, black and/or as exemplifying some curious or perhaps dangerous genetic trait or weakness.

performing health examinations, peering into microscopes, giving instruction to groups or simply behaving in a healthy fashion, by say riding a bike. However women more often then men were pictured as young, naked, infirm, black and/or as exemplifying some curious or perhaps dangerous genetic trait or weakness.

The “damsel in distress” of the pulps was more a “damsel of devolution” in college biology textbooks, not there to be rescued, but scientifically managed, shunned and sterilized.

CONCLUSION

Starting in the mid-1930s, a few high school and college biology textbook authors began to actively counter common stereotypes, at least concerning race and class. At the college level, James Watt Mavor’s General Biology (1936) stands out, as do Ella Thea Smith’s Exploring Biology (1938), Ernest Bayles and R. Will Burnett’s Biology for Better Living (1941) and Benjamin Gruenberg’s Biology and Man at the high school level. However, biology textbooks, particularly those intended for college audiences, remained remarkably retrograde through the 1940s and 50s in their use of common tropes to promote a biologized and naturalized view of existing class, gender and racial relationships.

In the 1950s and 60s, as biology textbook authors began to dial back their use of broad and humiliating visual tropes, Men’s Adventure magazines went all in. Violence against and violence by women spiked. The “Nazi torturer” became a favorite topic. And it became harder and harder to tell what the torturer represented: foreign evil, foreign women, women in general or the reader himself. However, by the end of the decade, no amount of sadism was sufficient to counter the pull of the porn rags and Soldier of Fortune magazine, which could deliver humiliation and domination in concentrated doses to hard-core addicts.

REFERENCES

Collins, Max Allan, George Hagenauer. 2008. Men’s Adventure Magazines in Postwar America. Hong Kong: Taschen.

De Laubenfels, M. W. 1949. Life Science. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Jean, Frank Covert, Ezra Calrence Harrah, Fred Louis Herman. 1952. Man and His Biological World. Boston: Ginn and Company.

Parfrey, Adam. 2003. It’s a Man’s World. Los Angeles: Feral House.

Stanford, E. E. 1947. Man & the Living World. New York: The Macmillan Company.